I am pushing through bodies. The airport is crowded and the line for taxis is long. Voices ring through the terminal, shouting to find lost family members in the jubilant chaos. I make my way through bumper-to-bumper traffic and walk along the highway until I spot my uncle’s car.

We are driving to Amman. Along the side of the road are endless rows of Palestinian flags. At my family’s home, we all crowd in my grandparents’ living room. My sido and teta sit at the center of the room, and my uncles, aunts and cousins surround them. Some members of the family want to stay, but my grandparents want to return.

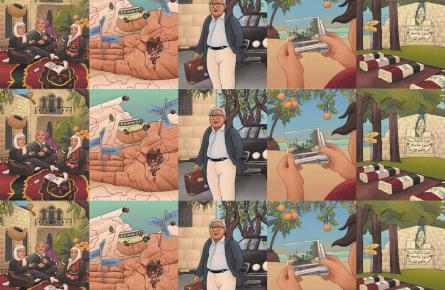

We take out all of our family documents. The pages are yellowed from time, the text is faded: the deed to our home in Palestine, refugee identity cards, various passports, the family tree. We prepare these documents meticulously. My grandparents insist on wearing their finest clothes.

We are driving. The closer we get to the border, the more intense the traffic. We abandon the car. My father helps sido get into his wheelchair; my cousins hold my grandmother's hands to support her as we begin our trek.

What was once a border crossing manned by soldiers is now a doorway to return guarded by our people. The lines are long but the volunteers do the best they can. They don’t turn anyone away. Each person presents their documents and is told “welcome home.” Young men facilitate dividing the refugees by region: “You from Tiberias, stand with the Northerners! You from Gaza, you from Ramla!” Convoys of buses and cars, driven by those who remained in the homeland, pick up the former refugees to take them to their hometowns and villages.

The bus to Ramla feels like a wedding; elderly women sing songs of victory, young men lead us with chants. We hear different languages echo between the seats: Swedish spoken by a young girl, Spanish from a family returning from Chile. Dialects of Arabic greet the new and the old, hailing from the Arab world and the diaspora. When the bus halts, we are met by a crowd of volunteers, ready to show us the way back to our villages.

We climb up the hills. I push my grandfather in his wheelchair. The road is bumpy but the wheels turn quickly, as if the land is pushing it forward, sensing my grandfather's excitement.

A metal gate has been pushed down. What was once a closed military zone is once again, a home. The buildings have been reduced to piles of rubble. But they are there. We hold each other and cry tears of joy, and tears of sadness for those who cannot be here with us. Then, the work begins.

We live with generous families in the city who allow us to stay with them as our village is rebuilt. All the young people partake in clearing out overgrown weeds, digging foundations, and finding old stone. The elders join us and sip tea, whispering prayers for our success.

The first home is rebuilt, then the next, then the next. Volunteers from other villages join us. We visit them and they visit us. When the work is done, we know we have not just rebuilt homes, or even just a village - we have rebuilt our homeland.

I imagine my family’s return to Palestine very often. Just as the story of my grandparents' displacement has come to define the lives of my parents and myself, I hope that the story of our return is what defines the lives of my children and grandchildren. It's time we begin to live everyday like our return is imminent within our lifetimes. It is feasible. Liberation is feasible. Return is feasible. Rebuilding the lives that were violently taken from our grandparents is feasible.

Historically, longing for return has been vital in maintaining the identity of Palestinian refugees, with the Nakba being the violent event experienced by our people that came to define our national experience. Keeping the right of return relevant has maintained our people's memories of towns and villages lost in 1948 alive amongst younger generations. I propose that we go further though. Imagining our return is not just a daydream, but a strategic exercise in preparation for what will one day be a reality. And let us be so radical as to envision our role in this preparation. How will we navigate physical return? Who will facilitate this return? Who will return? What will happen upon our return? Imagining liberation and return is a framework that allows Palestinians to organize accordingly; imagining return is the first step in actualizing it.

This has already been practiced in the past. Palestinian poet and martyr Ghassan Kanafani took us on this intense thought exercise with his short story, “Returning to Haifa.” While not in the context of a liberated Palestine, the refugee couple return to their home. Their experience of return propels them into political conclusions; they return to their exile with a renewed appreciation for the efforts undertaken by Palestinian resistance to actualize return. And Kanafani himself, partaking in this radical imaginative exercise, ensured that his writing was a catalyst for his own resistance.

Imagining return is crucial for both honoring our past and resisting in the present. One of the major critiques of the Palestinian Authority and the insistence on the Oslo paradigm is how refugees and their rights have been intentionally marginalized. Imagining return is itself a post-Oslo paradigm. A rejection of compromise and an embrace of a political and human framework that centers our past, our present, and our future. Looking at the ongoing settler-colonialism in Gaza, Akka, Jerusalem, Masafer Yatta, and other Palestinian cities and villages through the lens of return makes clear exactly what our goals as a people should be: the entirety of our land and the dignity of our people. Viewing these events through the Oslo framework that excludes refugees, return and the Nakba has yet to halt Israel’s occupation.

Let us imagine return, and let us work to actualize it.